Last November science educator Raven Baxter got a message from one of her former students. The student was studying for a final exam at S.U.N.Y. Buffalo State College and had questions about the immune system. Baxter—who will soon join the faculty of the School of Biological Sciences at the University of California, Irvine—decided to help. But instead of e-mailing the answers, she opened an app on her phone and wrote a song.

A few days later, Baxter, who performs as Raven the Science Maven, released an updated version of “The Antibody Song” to the tune of rapper Megan Thee Stallion’s “Body,” a hit that resonated with many pandemic-weary listeners and inspired multiple trends on TikTok. Baxter’s song went viral, teaching nearly three million listeners across several platforms about B cells, macrophages and opsonization.

With a significant portion of U.S. media consumption occurring on social platforms, Baxter’s approach illustrates the value of combining entertainment and education to reach broader audiences in the COVID-19 era. In a survey of more than 1,500 U.S. adults conducted by the Pew Research Center in January and February, 81 percent of respondents reported watching content on YouTube, compared with 56 percent who reported watching satellite or cable TV. And social media users, rather than traditional authorities, create most of the health content that visitors click on, says public health researcher Corey Basch of William Paterson University.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

In the past year, several public health organizations, aware of these trends, have partnered with online creators to leverage their audiences and expertise on social platforms. The Texas Department of State Health Services, for instance, has reached tens of millions of social media users by working with influencers to share factual information about COVID-19, according to a report in PRWeek. And the Ad Council raised $50 million for a campaign to educate people about the vaccine, including on social media platforms, the Washington Post reported.

In other cases, institutions and individuals have chosen to create their own COVID-19 health and vaccine information, tailoring it to the needs and interests of their particular audience and often posting the content on social platforms. Regardless of their genesis, many successful videos seek to foster a strong sense of trust and community among creators and their viewers. Social platforms often enable that communication strategy better than traditional media.

A sense of trust appears to be relevant to vaccination campaigns specifically. A systematic review of more than 1,100 studies on vaccine hesitancy published between 2007 and 2012 suggests that social influence plays a more reliable role than health information in one’s decision to get vaccinated. In regions ranging from the Democratic Republic of the Congo to Switzerland, the researchers identified key variables, including encouragement from others and a belief that vaccination should be a social norm.

Baxter was surprised when “The Antibody Song” went viral. “I honestly thought the song was horrible,” she recalls. But she had added images, captioned the lyrics and posted it anyway. “Part of earning people’s trust is being a little vulnerable and letting people get to know who you are,” Baxter says.

The videos below were posted on social media platforms. They illustrate successful communication strategies that build trust between viewers and creators to convey public-health information about COVID-19.

In this video, released in April, science communicator, YouTuber and best-selling author Hank Green addresses COVID-19 vaccination concerns that have circulated among young people. Green shared the video, which has been viewed nearly 200,000 times, on the Vlogbrothers channel, where he and his brother, John Green, have regularly posted content since 2007. Nearly four million YouTube users currently subscribe to the channel.

For a more recent project, Hank Green paid a musician to change three lines of Imogen Heap’s 2005 single “Hide and Seek” to a provaccine message. “I think that probably actually motivated more people than a reasoned argument,” he says. “Honestly, what seems to work more than arguments is enthusiasm.” Green’s video featuring that audio has been viewed nearly 800,000 times on TikTok.

Building trust with an audience is a slow, unpredictable process that can yield a stronger connection through sustained engagement on multiple platforms, Green says. Social platforms enable that process by allowing creators “to have many different points of contact with people over a long period of time,” he adds.

Featured on a channel with nearly 10 million subscribers, this AsapSCIENCE video is among YouTube’s most viewed pieces about COVID-19 vaccines. The channel’s hosts, Mitchell Moffit and Gregory Brown, are openly queer creators who share science-themed videos for a younger audience that tackle topics that include sexuality, recreational drug use and viral memes, such as the 2018 “Yanny-Laurel” audio clip. In a recent survey of 5,000 people who view science videos on YouTube, nearly half said they sometimes watch one simply because they like the content creator. And the respondents said they find the identity of a video’s host more important than the experts interviewed or the creator’s scientific background.

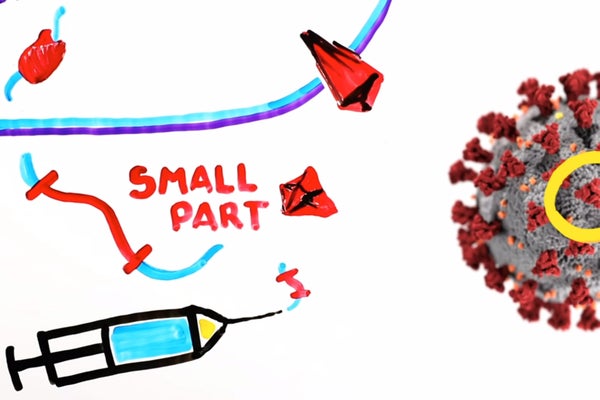

This video is produced in AsapSCIENCE’s typical style: a combination of narrated whiteboard drawing and “talking head” commentary from Moffit and Brown. The majority of the video explains how mRNA vaccines work. But it ends with a moment of trust-building vulnerability from Brown, who tells viewers, “We know you’ve been asking about these vaccines a lot. We’ve also had our questions, so we hope all this information ... does sort of help make things seem less unknown and scary in a very strange time.”

Puerto Rican science communicator Edmy A. Ayala Rosado starts this video by saying, in Spanish, that “vaccination is an act of solidarity” that also protects people who cannot get vaccinated. Such community-centered framing is more culturally relevant than standard public health messaging from agencies such as the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, says Mónica Feliú-Mójer, director of communications at Ciencia Puerto Rico, which produced the video. Government messaging “doesn’t necessarily align with the culture or the way that people think or carry on their daily lives” in Puerto Rico, Feliú-Mójer says. To fill that gap, Ciencia Puerto Rico, a nonprofit community group that advances science on the island, has produced a large selection of videos, graphics and other media about staying safe during the pandemic for Puerto Ricans to share with their communities and followers. The project began with conversations among Ciencia Puerto Rico team members and local leaders about community needs. Experts, including public health officials, often center public health messages on the topics and perspectives that are most important to them, says Kaytee Canfield, a researcher who recently co-authored a report on inclusive science communication for the Metcalf Institute. But these approaches can be ineffective if they do not resonate with a community that creators aim to reach, she adds.

@lab_shenanigans lemme yeet coronavirus outta here ��

♬ Yeet - Saturday Night Live - SNL

When postgraduate research technician Darrion Nguyen started posting on TikTok in mid-2019, he adapted the format of his popular Facebook and Instagram videos about science and lab life to fit the new platform. Instead of remixing other widely shared videos and audio clips to comment on his everyday experiences, Nguyen applied them to biochemistry or science concepts. This video, uploaded shortly after the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s December 2020 authorization of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine for use in adults, has been viewed 1.6 million times. It depicts an imaginary meeting between the vaccine’s first and second doses inside the body. The “doses” enthusiastically rap to an audio clip that was popular on TikTok at the time, ultimately intimidating a sheepish coronavirus that appears toward the video’s end.

Its public health message requires familiarity with content trends on TikTok. But such targeted approaches can be a potent tactic in vaccination discussions, according to a 2020 analysis of social networks among Facebook accounts. By mapping connections among nearly 100 million users and showing how they clustered within larger networks, the researchers found that antivaccine advocates formed a large number of small communities that collectively offered a broad range of narratives, which may have helped them spread their message. That range gave undecided users a variety of opportunities to engage with antivax content that was relevant to them, the study suggests. “These folks know the importance of people feeling like they belong in the community,” Canfield says.

Embracing the range of styles and narratives that are popular on social platforms is difficult for many public health officials, Basch says. “It’s very hard for someone who’s traditionally trained in the sciences to accept the fact that a 17-year-old influencer who’s doing wild things on TikTok is going to be [someone] we instill our trust in with our message,” she says.