Oceanographers are fond of saying that we know more about the moon's surface than we do about Earth's seafloor. It's true. As of 2017, only 6 percent of the global seabed had been mapped, typically by ships with sonar instruments sailing back and forth in straight lines across a local section of sea.

MILLION MOUNDS CORAL PROVINCE

NORTH ATLANTIC, 100 MILES EAST OF GEORGIA, U.S.

Investigators at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration have finished mapping the “million mounds” deep-sea province. Thousands of coral mounds, each 30 to 300 feet high, blanket 11,000 square miles of ocean floor, making it the largest deep-sea coral ecosystem ever discovered. At a depth of 2,000 to 2,600 feet, the seafloor receives no sunlight, so the white corals don’t house symbiotic algae that give shallow reefs their color. When old corals in the mounds die, their skeletons provide the foundation for new corals; some mounds have been growing for thousands of years.

Credit: Maciej Frolow

But since then, nations have become eager to chart the seafloor within their own “exclusive economic zones,” which reach 200 nautical miles from their shores, in part to look for critical minerals they can scrape up using big mining machines. The other push is Seabed 2030—an effort to map Earth's entire seafloor by 2030, run jointly by the Nippon Foundation and the nonprofit General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

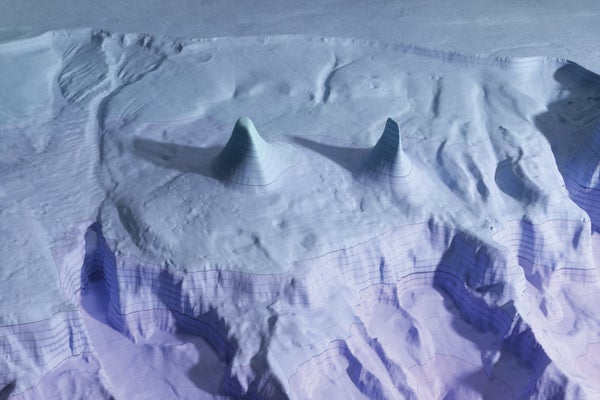

RYDER GLACIER SILL

Geologists at Stockholm University were puzzled about why the front edge of Ryder Glacier, at the Sherard Osborn Fjord, was losing less ice than the faces of other Greenland glaciers. Using multibeam sonar on an icebreaker in the fjord, they discovered two parallel sills of bedrock (red), separated by a basin, that cross the fjord. The inner sill, about 3.8 miles across and 1,600 to 1,900 feet high, blocks relatively warm Atlantic Ocean water from reaching the glacier and melting its underside, slowing the glacier’s demise.

Credit: Maciej Frolow

The goal is to collect and stitch together mapping done by governments, industries and research institutions everywhere. Public release of previously private bathymetric data is helping to widen the areas plotted. And uncrewed, remotely operated vehicles fitted with sonar that can zoom around underwater for days at a time are speeding the pace of mapping. By June 2022 an impressive 21 percent of the world's seafloor had been charted. The more experts map, the more surprises they find—such as the three unexpected, unusual formations revealed here.