Spanning millions of square miles, the Amazon rain forest is home to more than 350 Indigenous ethnic groups, each with a culture as rich and complex as the forest’s own tangled roots. But as non-Indigenous forces encroach on the region at an ever-accelerating rate through deforestation, poaching, mining and land grabs, many Indigenous groups have had to stand their ground against the rising tide of colonial destruction.

For more than two decades, photographer Sebastião Salgado has made it his mission to document the lives of the Amazon’s Indigenous peoples as they have both adapted to an increasingly modernized world and held fast to their culture and tradition. His striking black-and-white prints are collected in his new book Amazonia, published by Taschen.

Salgado, a Brazilian expatriate who now resides in Paris, first visited an Indigenous community in the Amazon when he traveled to a Yanomami village in the mid-1980s for a short documentary project. He was struck by the warmth and kindness with which the Yanomami people received him. Salgado returned a decade later, camera in hand, and would go on to spend a cumulative six years living with and learning from dozens of distinct Amazonian cultures alongside his wife, crew and translators.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Along the way, Salgado has become a staunch advocate for Indigenous sovereignty and environmental protections in this remarkable region. In 1998 the award-winning photographer and his wife founded Instituto Terra, a nonprofit organization dedicated to reforesting and protecting the Amazon in the Brazilian region of Vale do Rio Doce.

Credit: © Sebastião Salgado; Courtesy of Taschen

Wewito Piyáko Asháninka, a member of the Indigenous Asháninka people, inspects an arrow. His daughter, wife and son surround him. Historically, the Asháninka traded heavily with the Incan empire, providing the mountain-dwelling Inca with forest products such as feathers, cotton and fine wood in exchange for metal and wool.

Credit: © Sebastião Salgado; Courtesy of Taschen

The Suruwahá people live in massive communal houses some 100 feet tall, nearly the height of a 10-story building. Each house, or oca, is named for its “owner” and architect—in this case, a man named Kwakway.

Credit: © Sebastião Salgado; Courtesy of Taschen

Chief Kotok, then leader of the Kamayurá people, wears traditional body paint. The Kamayurá, along with other cultures native to the Xingu region of the Amazon rain forest, create elaborate and gender-specific patterns with paint, highlighting their physical attributes.

Credit: © Sebastião Salgado; Courtesy of Taschen

Wewito Piyáko Asháninka fishes by standing in a canoe and casting his net into the river. The traditional kushma tunic he wears once sported vertical stripes but has been dyed dark brown as the colors have faded.

Credit: © Sebastião Salgado; Courtesy of Taschen

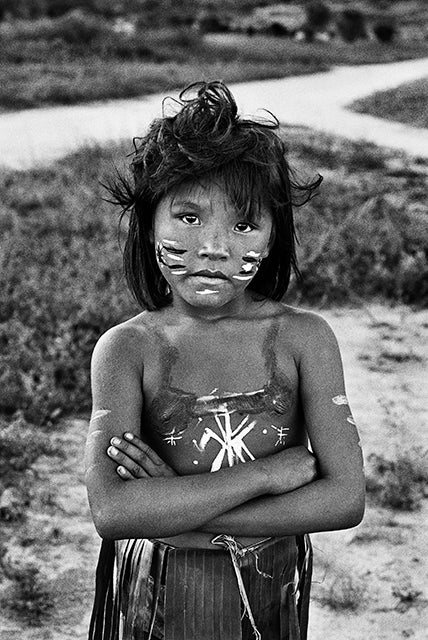

Andecleia Macuxi lived in the town of Maturuca, Brazil, in 1998, when this photograph was taken. At the time, the Macuxi people were fighting for the right to reclaim their own land, which was finally recognized by the Brazilian government in 2009. Today Andecleia lives in the village of Mutum.

Credit: © Sebastião Salgado; Courtesy of Taschen

These brilliant hyacinth macaws, photographed in Jaú National Park in the Brazilian state of Amazonas, have the largest wingspan of any parrot on the planet. Their beauty and size make them frequent targets for poachers to sell in the black-market pet trade. Today an estimated 6,500 individuals exist in the wild.

Credit: © Sebastião Salgado; Courtesy of Taschen

Biraci Brasil (center), also known as Bira, assumed leadership of the Yawanawá people in the early 1990s, after decades of abuse from colonizers. “Our beliefs and traditions were considered demonic by the missionaries and a lot of us believed it. We began to live as slaves, at work and culturally,” he told Salgado.

Credit: © Sebastião Salgado; Courtesy of Taschen

The Yanomami people represent the Americas’ largest low-contact Indigenous group. Like many Yanomami communities, the village of Watoriki is surrounded by lush, curated forest and is constructed in a ring encircling a central courtyard where celebrations and rituals are held.

Credit: © Sebastião Salgado; Courtesy of Taschen

Alzira is a member of the Yawanawá people, a group that has, since the 1970s, rebounded from 120 members to more than 1,200 as a result of hard-won Indigenous sovereignty. In their native language, Yawanawá means “white-lipped peccary people.”

Credit: © Sebastião Salgado; Courtesy of Taschen

The Marubo people make their homes along the Curuçá River in the western Amazon. Like much of the Amazon, this region is prone to heavy rains and seasonal flooding. Salgado first visited the region in the late 1990s to help document a hepatitis outbreak.

Credit: Amazônia, by Sebastião Salgado; Courtesy of Taschen