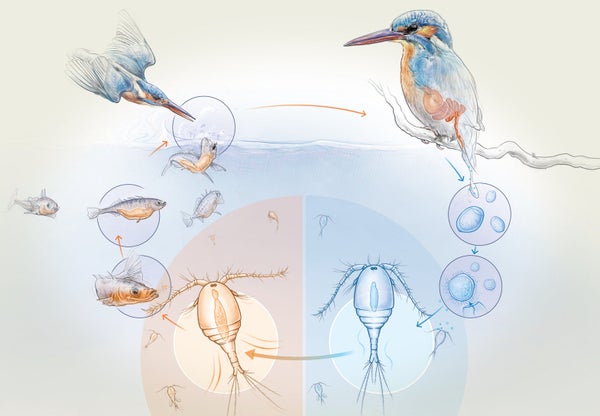

Parasites give new meaning to the cliché “eat or be eaten.” Often their life cycle can be completed only if they are ingested by a host—multiple times for some—making the odds of their survival seemingly minuscule. To improve their chances, certain parasites manipulate their hosts' behavior to make it more likely the eater will get eaten.

The parasitic cestode Schistocephalus solidus requires a much larger host—specifically, a three-spined stickleback fish—to grow in and then a bird to breed in. But the parasite's larvae, less than a millimeter long, are too small to be eaten by the fish.

Instead a larva must first be ingested by a copepod, a crustacean akin to a tiny shrimp. When ready for its next host, the larva makes the copepod twitch. If all goes well (for the parasite), a three-spined stickleback then eats the copepod. Inside the fish, the larva grows enormously, making the poor stickleback gasp at the water's surface, where it is likely to get snacked on by a bird. Inside the bird, the parasite matures and mates, sending its eggs back to the water through the bird's poop. And so the cycle begins again.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

.png?w=900)

Credit: Daisy Chung