Climate change is already disrupting the lives of billions of people. What was once considered a problem for the future is raging all around us right now. This reality has helped convince a majority of the public that we must act to limit the suffering. In an August 2022 survey by the Pew Research Center, 71 percent of Americans said they had experienced at least one heat wave, flood, drought or wildfire in the past year. Among those people, more than 80 percent said climate change had contributed. In another 2022 poll, 77 percent of Americans who said they had been affected by extreme weather in the past five years saw climate change as a crisis or major problem.

Yet the response is not meeting the urgency of the crisis. A transition to clean energy is underway, but it is happening too slowly to avoid the worst effects of climate change. The U.S. government finally took long-delayed action by passing the Inflation Reduction Act in August 2022, but much more progress is needed, and it is hampered by entrenched politics. The partisan divide largely stems from conservatives’ perception that climate change solutions will involve big government controlling people’s choices and imposing sacrifices. Research shows that Republicans’ skepticism about climate change is largely attributable to a conflict between ideological values and often discussed solutions, particularly government regulations. A 2019 study in Climatic Change found that political and ideological polarization on climate change is particularly acute in the U.S. and other English-speaking countries.

One thing we can all do to ease this gridlock is to alter the language and messages we use about climate change. The words we use and the stories we tell matter. Transforming the way we talk about climate change can engage people and build the political will needed to implement policies strong enough to confront the crisis with the urgency required.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Words Matter

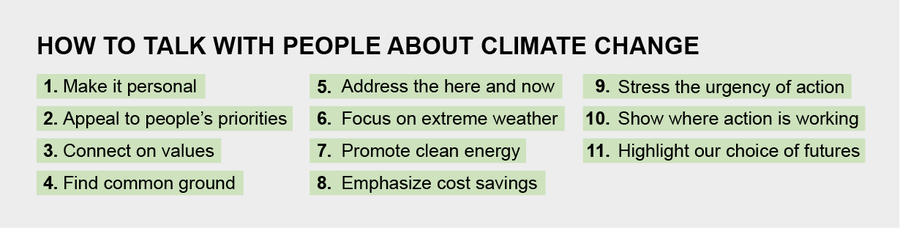

To inspire people, we need to tell a story not of sacrifice and deprivation but of opportunity and improvement in our lives, our health and our well-being—a story of humans flourishing in a post-fossil-fuel age.

Some of the language problems we face in presenting this story are inadvertent and innocent, such as how scientists use jargon and think the facts speak for themselves. Others are intentional and insidious, such as the well-funded disinformation campaign led by the fossil-fuel industry that is meant to confuse, obfuscate and mislead.

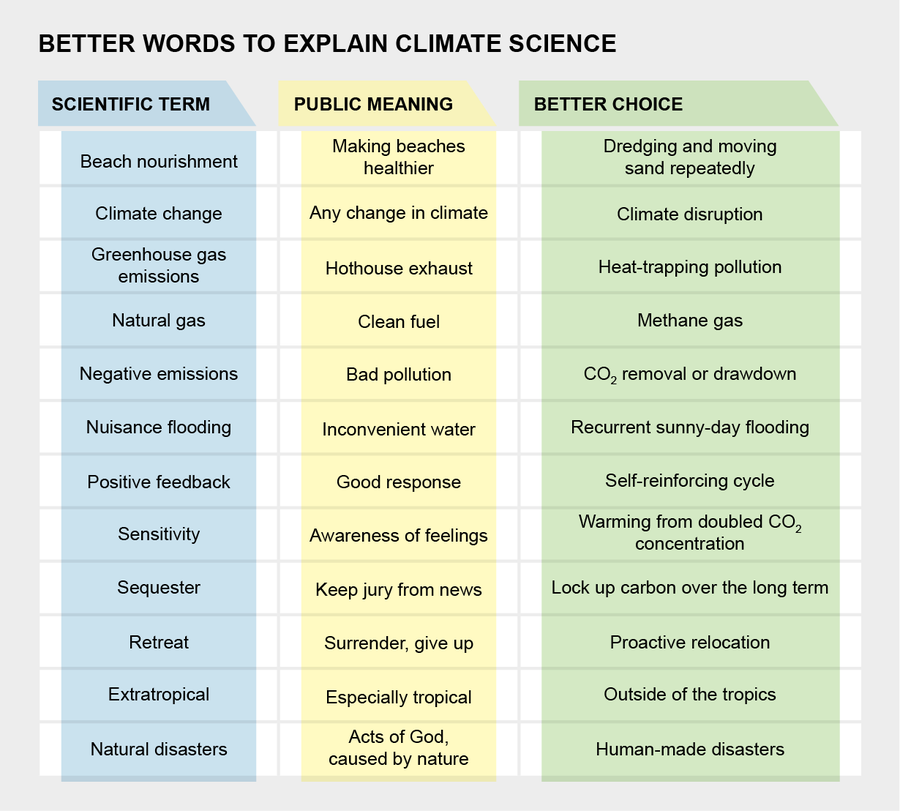

Jargon can be hard to understand, but even worse are familiar terms that in a scientific context have entirely different meanings. For example, people generally use “positive” to mean “good” and “negative” to mean “bad.” But climate scientists use “positive” to mean “increasing” and “negative” for “decreasing.” So a positive trend in temperature means it’s going up—not good in an era of global warming. Scientists also speak of negative emissions, which sounds like bad pollution but in fact refers to the removal of carbon dioxide from the air—a good thing! It would be clearer to call these efforts CO2 removal, uptake or drawdown.

Perceptions can be greatly influenced by the words we use. “Natural” commonly refers to things occurring in nature that are not influenced by humans. But many events we call natural disasters—such as torrential rains and more powerful hurricanes that lead to severe flooding or extreme heat and drought that exacerbate wildfires—are no longer entirely natural. By disrupting climate and erecting buildings in vulnerable locations, humans are creating unnatural disasters. The word “natural” can be exploited in other ways, too. In 2021 researchers at Yale University found that Americans associate natural gas with “clean” and methane gas with “pollution”—even though natural gas is almost entirely methane.

Credit: Susan Joy Hassol, styled by Scientific American

The language we use for climate solutions can exacerbate the cultural divide. Terms such as “regulate,” “restrict,” “cut,” “control” and “tax” are unpopular, especially among conservatives. Perhaps people would be more likely to support solutions described with words such as “innovation,” “entrepreneurship,” “ingenuity,” “market-based” and “competing in the global clean energy race.” The fact that the first significant U.S. climate policy is called the Inflation Reduction Act is another example of how word choice matters. The name itself helped to gain the crucial support of Senator Joe Manchin of West Virginia, the swing vote. The name may also have made the legislation more appealing to the many Americans who worry about climate change but rank it below inflation and the economy on their list of priorities.

Changing other words can help inform people and redirect the climate conversation. Instead of referring to greenhouse gases, we can refer to “heat-trapping pollution.” That term reinforces the basic mechanism of human-caused climate change, and “pollution” has negative associations, which are appropriate in this context. “Climate change” has become pretty standard, but a better description of what we’re experiencing is “human-caused climate disruption.” Sadly, “climate crisis” and “climate emergency” are accurate, too.

In low-lying coastal areas, seawater increasingly fills the streets at high tide, even on days with no rain. The costs are enormous: cities such as Miami spend hundreds of millions of dollars on systems to pump the water out. Yet experts call this “nuisance flooding,” greatly understating its human and monetary impacts. It might more appropriately be referred to as “sunny-day” or “recurrent” flooding. Similarly, as sea level rises and stronger hurricanes hit, we are beginning to hear calls for “managed retreat” from the coasts. But that sounds too much like surrender. As military generals have been known to say, we never retreat; we just advance in a different direction. It would be more positive to call for “proactive relocation” to safer, higher ground.

Taking on the challenges

Word choice is part of the broader set of communication challenges we must face to build the political will needed to swiftly address the climate crisis. We can group the challenges into disinformation, misconceptions and the pigeonholing of climate change as an environmental issue. Let’s take disinformation first.

The fossil-fuel industry and those who do its bidding have executed a well-funded, long-running disinformation campaign that takes advantage of the confusion around climate language. The people behind this campaign know that scientists use “theory” to mean an idea that is very well established in science, but to the public, a theory is just a hunch. They also know that to the public, “uncertainty” is synonymous with “ignorance,” even though scientists use the term to refer to a range of possible results. So fossil-fuel advocates endlessly repeat: “Climate change is only a theory. There’s so much uncertainty.”

As the climate crisis has increasingly affected our daily lives, it has become more difficult to deny its reality. That’s why people guarding the status quo have changed tactics, shifting from denial of climate science to strategies such as deflection—for example, getting us to focus on our own personal carbon footprints rather than examining the huge role of big oil and gas companies in delaying climate action. They also sow doubt by promoting myths and lies about solutions—they’re too expensive, they’re unreliable. Donald Trump told a crowd in 2019 that if a “windmill” were erected anywhere near their house, their home value would drop 75 percent, and the noise would cause cancer.

Credit: Susan Joy Hassol, styled by Scientific American

One way to counter disinformation is to get ahead of it by “inoculating” the public—promoting accurate information and helping people recognize disinformation techniques. Researchers have determined that preemptive messages explaining disinformation techniques while highlighting correct information can be effective in preventing misunderstanding. One key fact to emphasize is that the cost of renewable energy has plummeted, making clean energy cheaper than dirty energy. The prices of solar power and batteries have fallen by about 90 percent in the past decade, and there have been steep declines in the cost of wind energy as well.

Good progress has also been made on managing variable energy sources such as solar and wind, as well as in storing the energy they produce. We’re not waiting for an energy miracle; we’ve already had one.

The second major challenge, often related to the first, involves widespread misconceptions about climate disruption and public perception. Research published in 2022 in Nature Communicationsshowed that although 66 to 80 percent of Americans support climate change policies, they think only 37 to 43 percent of the population does; they believe the climate-concerned community is a minority, when in fact it’s a majority. The researchers also found that although supporters of policies to limit climate change outnumber opponents two to one, Americans falsely perceive the opposite to be true. This false social reality tends to limit how much people talk about the subject, and it decreases motivation and political pressure to pursue climate policies. One response is simply to talk about climate change more with family, friends, co-workers, and leaders in the public and private sectors. Each of us can be part of this solution.

There’s also a growing misconception that it’s too late to act—that global climate catastrophe is inevitable. This may result, in part, from the media’s focus on disasters rather than solutions, which can make many people feel a sense of hopelessness or fatalism. A 2021 study in the Lancet revealed that young people are especially vulnerable to these feelings, with 84 percent saying they’re worried and 75 percent saying they think the future is frightening. If people are convinced we’re doomed— that there’s nothing we can do—why would they bother trying? It is imperative that we clearly communicate that it is not too late to avoid the worst outcomes. We must act urgently because every delay means a hotter and costlier future. Every fraction of a degree matters, and every action matters. As climate activist Greta Thunberg of Sweden so aptly put it, “When we start to act, hope is everywhere.”

People who feel constructive hope (as opposed to passive hope, such as that “God will save us”) are more likely to act and support climate policies, according to a 2019 study by researchers at Yale and George Mason University. Raising feelings of hope involves boosting a sense of efficacy—that what we do as individuals and as a society can truly make a difference. Rather than promoting stories of doom and deprivation, we can tell stories that illustrate the many benefits we will reap from the clean energy transition and from protecting nature. We need to paint a picture of that better world—powered by renewable energy, with friendlier, more walkable cities—and show how and where the improvements are already unfolding. It’s psychologically important for people to know that we’re not just starting; we’re already on our way.

The third challenge is that climate disruption has for years been categorized as an environmental issue. A 2021 Gallup survey found that only 41 percent of Americans consider themselves environmentalists. And environmental issues, especially climate change, have become so politically polarized that some people are hostile to any discussion of them.

The reality is that everyone cares about something affected by the climate emergency. Are they people of faith? Climate disruption is damaging God’s creation and disproportionately hurting people who are “the least of these.” Do they like to fish? Climate change is warming up our rivers, reducing the habitat for cold-water species such as salmon and trout. Are they skiers? Warming is reducing winter recreation opportunities. Everyone has to eat, and climate change is taking a toll on some of our favorite things, such as coffee and chocolate, as well as important staple crops, including corn and wheat. Many people are suffering from rising summer heat and humidity, wildfire smoke, and other aspects of increasingly extreme weather. The next time you want to talk with someone about climate disruption, consider what they care about and use that as an entry point. As with most good communication, success depends on the ways we connect on values, build trust and find common ground.

If you know that someone’s group allegiance leads them to reject the notion of human-caused climate change, rather than banging your head against a locked front door, look for a side door. For example, almost everyone likes clean energy, and for good reason. It offers clean air and water, energy security, reduced costs, job creation, and more. So even without invoking climate change, there are many reasons to support deploying clean energy. A 2015 study in Nature Climate Change showed that across 24 countries, action on climate change was motivated by other benefits, notably economic development and healthier communities. A 2022 study in Nature Energy compared three ways of framing renewable energy’s benefits—cost savings, economic boost and climate change mitigation—and found that cost savings was the most effective frame across political groups. One ironic example: in 2017 the Kentucky Coal Museum covered its roof with 80 solar panels because the technology saved the organization money.

Making the changes necessary to avoid the worst impacts of climate disruption will require sufficient social support before the world crosses too many dangerous climate thresholds. Research published in 2018 in Science suggests large-scale social changes require the active engagement of about 25 percent of the population. Surveys suggest that in the U.S. we are rapidly approaching that point on climate. Researchers at Yale and George Mason found that as of late 2021, one third of Americans were alarmed about the climate crisis, and most of them were willing to act.

Addressing climate communication challenges could help us build enough political will in time to blunt the worst climate change effects. People must grasp the urgency of the choice we face between a future with a little more warming and global catastrophe. And they need to recognize that the choices we make now will determine our fate.