1972

Neutrino Trap

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

“It is believed that the sun's radiant energy originates with thermonuclear reactions deep in the interior. One product should be a flood of neutrinos: massless, uncharged particles that interact so little with other particles that solid bodies such as the earth are virtually transparent to them. Raymond Davis, Jr., of the Brookhaven National Laboratory has devised a detector to test the theory. It is buried a mile under solid rock in the Homestake Gold Mine in Lead, S.D., a huge tank containing 100,000 gallons of the dry-cleaning solvent tetrachloroethylene, 85 percent chlorine. When a neutrino is absorbed by an atom of chlorine, an atom of the radioactive isotope argon 37 is formed. At intervals of about 100 days the tank is swept with helium gas to remove the argon 37. Theory predicts that neutrinos are produced at such a rate that Davis's detector should capture two neutrinos per day. Results over the past two years show that the capture rate is less than 0.2 neutrino per day. Explanations of the discrepancy are varied, but none is very satisfactory. The problem is certain to receive intense study in the near future.”

1922

Guatemala in Two Acres

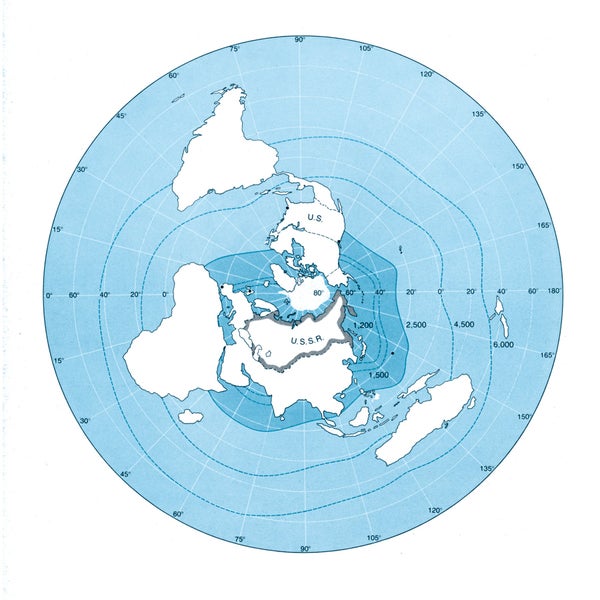

“The republic of Guatemala, to make it easy for visiting capitalists to decide on proposed investments, has built what seems by all odds the most extraordinary relief map in the world. This map is two acres in extent, and shows every contour, every town and every stream or lake in Guatemala and the neighboring territory of British Honduras. The giant topographical map is of concrete, assembled in sections. Almost two years were spent making the molds, and checking them up. The ultimate cost was $100,000, and another like sum was spent in gathering the data on which the map is based. The big map is located in the hippodrome, or racetrack, at Guatemala City, and it has passed through two earthquakes without harm.”

The map still exists, albeit as a tourist attraction.

We Ought to Be in Pictures

“Scientific American has entered the motion picture field, as producers of Scientific American films, in collaboration with the Coronet Films Corporation of Providence, R.I. The films, which will appear once a month, will be shown in theaters throughout the country. Subjects will be taken from our columns and transplanted to the screen. We also have inaugurated a special radio-phone broadcasting talk in order that we might report and comment on the scientific news of the day. We are using the WJZ station of the Radio Corporation-Westinghouse organizations, located at Newark, N.J., covering a range of several hundred miles. In the very near future we shall make arrangements to cover more or less the entire country.”

1872

Solar System Causes Cholera

“B. G. Jenkins recently read, before the Historical Society of London, a remarkable paper, in which he maintained that cholera is intimately connected with [the cycle of sun spots, which has a period of 11.11 years]. He said, ‘Cholera epidemics have, I believe, a period equal to a period and a half of sun spots. The date 1816.66 was shortly before the great Indian outbreak; another period and a half gives 1833.33, a year in which there was a maximum of cholera; another, 1849.99, that is, 1850, a year having a maximum of cholera; another, 1866.66, a year having a maximum of cholera; in 1883.33 there will be a maximum. I am not prepared to say that sun spots originate cholera; for they may both be the effects of some other cause. My own opinion is that planets, in coming to and going from perihelion—more especially about the time of the equinoxes—produce a violent action upon the sun [producing] a maximum of sun spots, and in connection with it a maximum of cholera on the earth.’”

Sanitary Lead Pipes

“Several citizens of Sacramento, Calif., having been poisoned by the use of what is known as the ‘sanitary composite’ water pipe. The Board of Health has ordered its use to be discontinued. Water flowing through this pipe was found, on chemical analysis, to contain lead and arsenic. The pipe in question is believed to be composed of a species of brass.”