The following essay is reprinted with permission from The Conversation, an online publication covering the latest research.

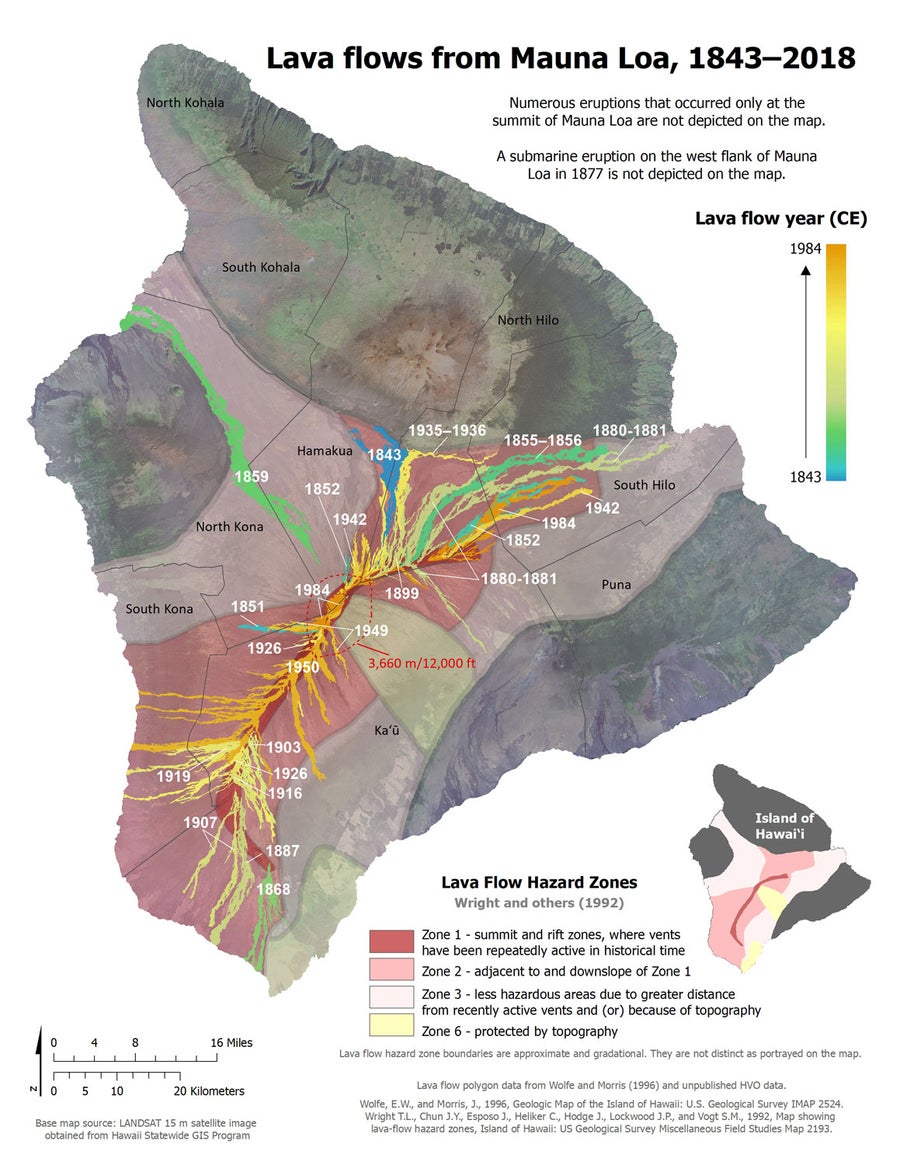

Hawaii’s Mauna Loa, the world’s largest active volcano, began sending up fountains of glowing rock and spilling lava from fissures as its first eruption in nearly four decades began on Nov. 27, 2022.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Where does that molten rock come from?

We asked Gabi Laske, a geophysicist at the University of California-San Diego who led one of the first projects to map the deep plumbing that feeds the Hawaiian Islands’ volcanoes, to explain.

Where is the magma surfacing at Mauna Loa coming from?

The magma that comes out of Mauna Loa comes from a series of magma chambers found between about 1 and 25 miles (2 and 40 km) below the surface. These magma chambers are only temporary storage places with magma and gases, and are not where the magma originally came from.

The origin is much deeper in Earth’s mantle, perhaps more than 620 miles (1,000 km) deep. Some scientists even postulate that the magma comes from a depth of 1,800 miles (2,900 km), where the mantle meets Earth’s core.

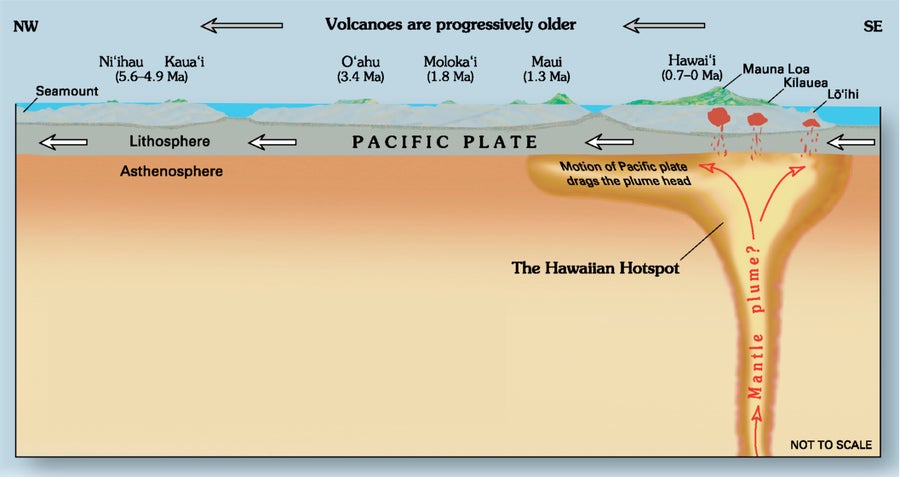

An illustration suggests what Hawaii’s mantle plume might look like. Credit: Joel E. Robinson, USGS

Earth’s crust is made up of tectonic plates that are slowly moving, at about the same speed as a fingernail grows. Volcanoes typically occur where these plates either move away from each other or where one pushes beneath another. But volcanoes can also be in the middle of plates, as Hawaii’s volcanoes are in the Pacific Plate.

The crust and mantle that comprise the Pacific Plate cracks at different places as it moves northwestward. Beneath Hawaii, magma can move upward through the cracks to feed different volcanoes on the surface. The same thing happens at Maui’s Haleakala, which last erupted about 250 years ago.

How does molten rock travel from deep in Earth’s mantle, and what exactly is a mantle plume?

Scientists hypothesize that the mantle is not made of uniform rock. Instead, differences in the type of mantle rock make it melt at different temperatures. Mantle rock is solid at some places, while it starts to melt at other places.

The partially molten rock becomes buoyant and ascends toward the surface. The ascending mantle rock is what makes a mantle plume. Because the overlying pressure lessens as the rock ascends, it melts more and more, and eventually collects in the magma chamber. If a large enough opening exists at the surface, and enough volcanic gases have collected in the magma chamber, the magma is forced to the surface in a volcanic eruption.

Seismic imaging by research teams I’m involved with has shown that Hawaii’s mantle plume comes from deep inside the mantle.

But the plume is not a straight pipe as some concept figures suggest. Instead, it has twists and turns, originally coming from the southeast, but then turning toward the west of Hawaii as the plume reaches into the shallower mantle. Cracks in the Pacific Plate then channel the magma upward toward the magma chamber beneath the island of Hawaii.

Why does Hawaii typically see less dramatic eruptions than other locations?

Hawaii is in the middle of an oceanic plate. In fact, it is the most isolated volcanic hot spot on Earth, far away from any plate boundary.

Oceanic magma is very different from continental magma. It has a different chemical composition and flows much more easily. So, the magma is less prone to clog volcanic vents on its ascent, which would ultimately lead to more explosive volcanism.

Thermal imaging shows the Mauna Loa eruption, which began around 11:30 p.m. local time on Nov. 27, 2022. Temperatures are in Celsius. Credit: USGS

How do scientists know what is happening under the surface?

Volcanic activity is monitored with many different instruments.

The perhaps simplest to understand is GPS. The way scientists use GPS is different from that of everyday life. It can detect minuscule movements of a few centimeters. On volcanoes, any upward movement on the surface detected by GPS indicates that something is pushing from underneath.

Even more sensitive are tiltmeters, which are in essence the same as bubble levels that people use to hang pictures on a wall. Any change in the tilt on a volcano slope indicates that the volcano is “breathing,” again because of magma moving below.

A very important tool is watching for seismic activity.

Volcanoes like Hawaii’s are monitored with a large network of seismographs. Any movement of magma below will cause tremors that are picked up by the seismometers. A few weeks before the eruption of Mauna Loa, scientists noticed that the tremors came from ever shallower depths, indicating that magma was rising and an eruption might be imminent. This allowed scientists to warn the public.

Other ways that volcanic activity is monitored includes chemical analysis of gases coming out through fumaroles—holes or cracks through which volcanic gases escape. If the composition changes or activity increases, that’s a pretty clear indication that the volcano is changing.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.