Long before COVID-19, scientists had been working to identify animal viruses that could potentially jump to people. These efforts have led to a Web-based platform called SpillOver, which ranks the risk that various viruses will make the leap. Developers hope the new tool will help public health experts and policymakers avoid future outbreaks.

Jonna Mazet, an epidemiologist and disease ecologist at the University of California, Davis, has led this work for more than a decade. It began with the USAID PREDICT project, which sought to go beyond well-tracked influenza viruses and identify other emerging pathogens that pose a risk to humans. Thousands of scientists scoured more than 30 countries to locate and identify animal viruses, discovering many new ones in the process. But not every virus is equally threatening. So Mazet and her colleagues decided to create a framework to interpret their findings. “We wanted to move beyond scientific stamp collecting [simply finding viruses] to actual risk evaluation and reduction,” she says.

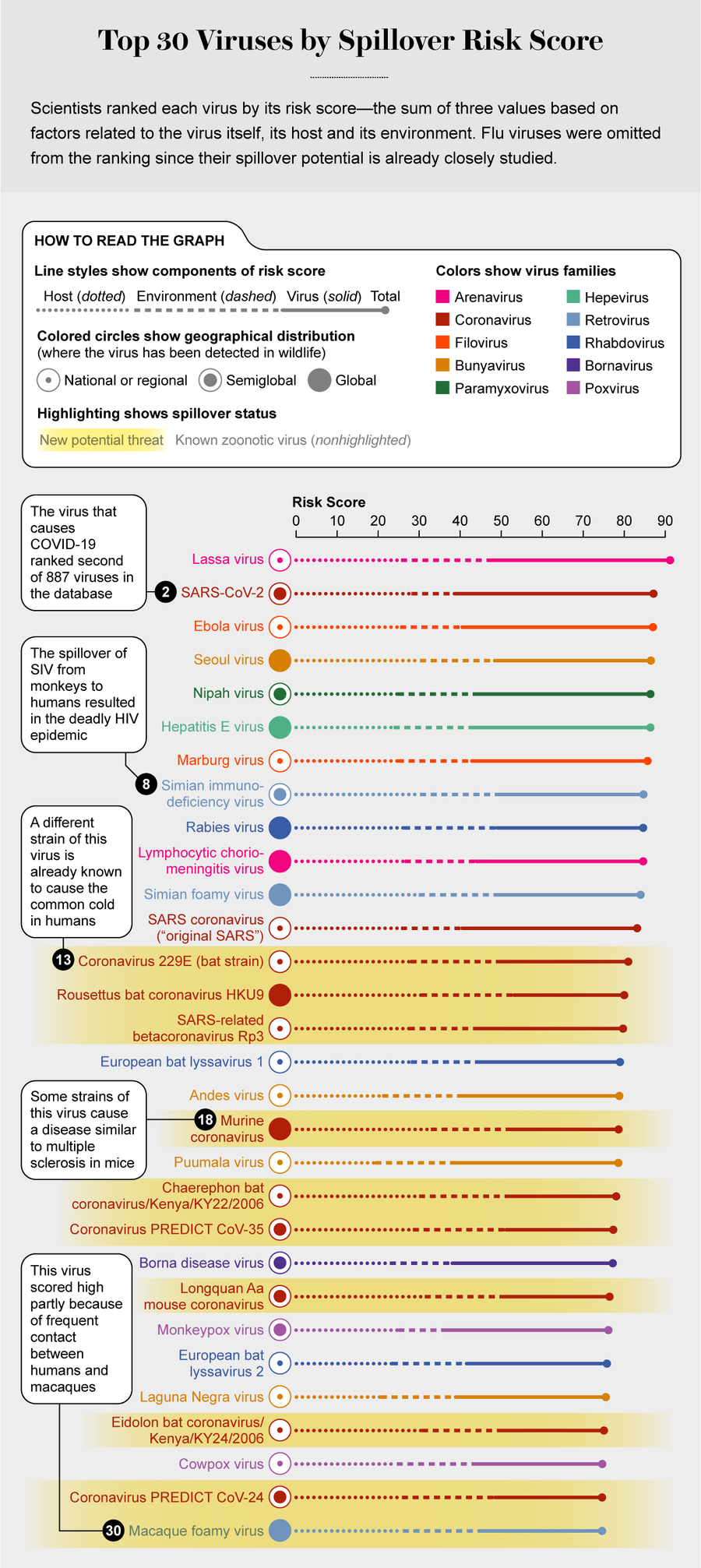

Credit: Amanda Montañez; Source: SpillOver (https://spillover.global); data as of April 7, 2021

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The team was surprised to find very little existing research on categorizing threats from viruses that are currently found only in animals but are in viral families that can likely cause disease in people. So the researchers started from scratch, identifying 31 factors pertaining to animal viruses (such as how they are transmitted), to their hosts (such as how many and varied they are), and to the environment (human population density, frequency of interaction with hosts, and more). These are summed up in a risk score out of 155; the higher the score, the more likelihood of spillover.

Cornell University virologist Colin Parrish, who was not involved in the study, says the factors examined were important in previous spillovers. But he notes that other viruses' crossover risk may be heightened by unforeseeable factors that crop up later. “It's a bit like the stock market,” he says.

The new study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, ranks 887 animal-borne viruses. Twelve known human pathogens scored at the top—with the virus that causes COVID-19 in second place, just under the rat-carried Lassa virus. (Influenza would have topped the list if included, Mazet says, but flu variants are already tracked elsewhere.) Parrish notes that the list also omits insect-borne viruses and those from domesticated animals. “This is a work in progress,” he says. “I'm sure it will be iterated into a more powerful tool as more information and data become available.

SpillOver is publicly editable, and scientists around the world are already contributing their own findings. Mazet hopes it catches the attention of public health practitioners and leaders, too. With targeted action, Mazet says, “we can ensure that we don't have these spillovers at all. Or if we do, we're ready for them—because we're watching.”