With the global population of humans well beyond seven billion, it is difficult to imagine that Homo sapiens was once an endangered species. Yet studies of the DNA of modern-day people indicate that, once upon a time, our ancestors did in fact undergo a dramatic population decline. Although scientists lack a precise time line for the origin and near extinction of our species, we can surmise from the fossil record that our forebears arose throughout Africa shortly before 195,000 years ago. Back then the climate was mild and food was plentiful; life was good. But around 195,000 years ago, conditions began to deteriorate. The planet entered a long glacial stage known as Marine Isotope Stage 6 (MIS6) that lasted until roughly 123,000 years ago.

A detailed record of Africa’s environmental conditions during glacial stage 6 does not exist, but based on more recent, better-known glacial stages, climatologists surmise that it was almost certainly cool and arid and that its deserts were probably significantly expanded relative to their modern extents. Much of the landmass would have been uninhabitable. While the planet was in the grip of this icy regime, the number of people plummeted, and only a subset contributed to the surviving population. Geneticists debate how small this population was, but it could have been as few as several hundred individuals. Estimates of the timing of the bottleneck tend to be at around 150,000 years ago. Given the narrow genetic diversity of modern humans, it seems likely that the main progenitor population was a single group, perhaps one ethnolinguistic group, that lived in one region and then spread outward, mixing with other populations as it moved.

I began my career as an archaeologist working in East Africa and studying the origin of modern humans. But my interests began to shift when I learned of the population bottleneck that geneticists had started talking about in the early 1990s. Humans today exhibit very low genetic diversity relative to many other species with much smaller population sizes and geographic ranges—a phenomenon best explained by the occurrence of a population crash in early H. sapiens. Where, I wondered, did our ancestors manage to survive during the climate catastrophe? Only a handful of regions could have had the natural resources to support hunter-gatherers. Paleoanthropologists argue vociferously over which of these areas was the ideal spot. The southern coast of Africa, rich in shellfish and edible plants year-round, seemed to me as if it would have been a particularly good refuge in tough times. So, in 1991, I decided I would go there and look for sites with remains dating to glacial stage 6.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

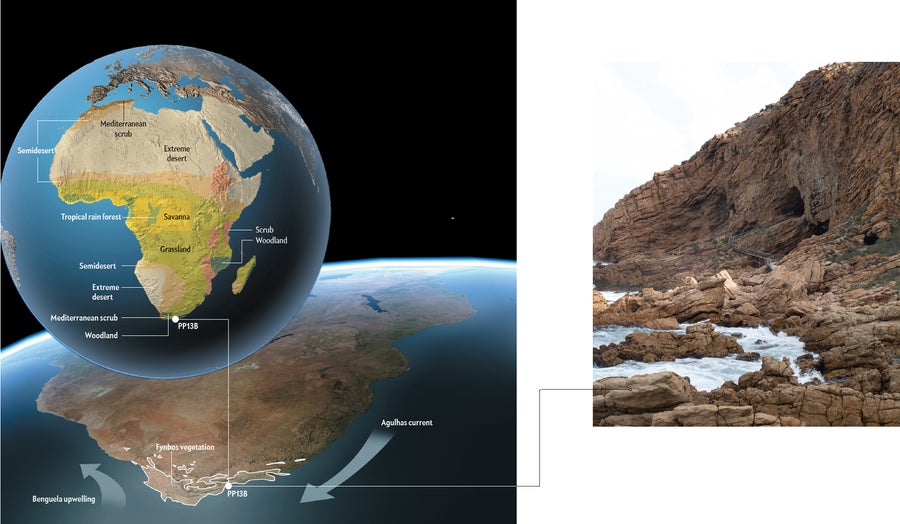

Seaside Sanctuary

Between 195,000 and 123,000 years ago, the planet was locked in an ice age known as Marine Isotope Stage 6, rendering much of the African continent cool and arid—unsuitable for the plants and animals that Homo sapiens ate. Only a few regions could have supported our species, namely, those with grassland or Mediterranean scrub vegetation. The southern coast would have been a particularly plentiful oasis, thanks to three rich resources—the edible fynbos plants that grow only here; the dense shellfish beds nurtured by the Agulhas current and the Benguela upwelling of nutrient-rich cold water from the sea bottom; and the populations of large mammals living on the exposed plain.

High and Dry

Finding archaeological sites dating to glacial stage 6 required searching for shelters that were close enough to the sea to allow relatively easy access to shellfish yet elevated enough that their ancient remains would not have washed away when the sea level rose 123,000 years ago. PP13B and other caves carved into the sheer cliff face of a promontory called Pinnacle Point meet those requirements and have yielded a plethora of remains dating to this critical juncture in human prehistory.

Credit: Don Foley (map), Lucy Reading-Ikkanda (globe); J. C. DE VYNCK Center for Coastal Paleosciences, Nelson Mandela University (image)

Since then, my team’s excavations at PP13B and other nearby sites have recovered a remarkable record of the activities undertaken by the people who inhabited this area between approximately 164,000 and 35,000 years ago, hence during the bottleneck and after the population began to recover. The deposits in these caves, combined with analyses of the ancient environment there, have enabled us to piece together a plausible account of how the prehistoric residents of Pinnacle Point eked out a living during a grim climate crisis. The remains also debunk the abiding notion that cognitive modernity evolved long after anatomical modernity: evidence of behavioral sophistication abounds in even the oldest archaeological levels at PP13B. This advanced intellect no doubt contributed significantly to the survival of the species, enabling our forebears to take advantage of the resources available on the coast.

While elsewhere on the continent populations of H. sapiens died out as cold and drought claimed the animals and plants they hunted and gathered, the lucky denizens of Pinnacle Point were feasting on the seafood and carbohydrate-rich plants and large mammals that proliferated there despite the hostile climate. As glacial stage 6 cycled through its relatively warmer and colder phases, the seas rose and fell, and the ancient coastline advanced and retreated. But so long as people tracked the shore, they had access to an enviable bounty.

A coastal cornucopia

From a survival standpoint, what makes the southern edge of Africa attractive is its unique combination of plants and animals. There a thin strip of land containing the highest diversity of flora for its size in the world hugs the shoreline. Known as the Cape Floral Region, this 90,000-square-kilometer strip contains an astonishing 9,000 plant species, some 64 percent of which live only there. Indeed, the famous Table Mountain that rises above Cape Town in the heart of the Cape Floral Region has more species of plants than does the entire U.K. Of the vegetation groups that occur in this realm, the two most extensive are the fynbos and the renosterveld, which consist largely of shrubs. To a human forager equipped with a digging stick, they offer a valuable commodity: the plants in these groups produce the world’s greatest diversity of geophytes—underground energy-storage organs such as tubers, bulbs and corms.

Geophytes are an important food source for modern-day hunter-gatherers, for several reasons. They contain high amounts of carbohydrate; they attain their peak carbohydrate content reliably at certain times of the year; and, unlike aboveground fruits, nuts and seeds, they have few predators. The bulbs and corms that dominate the Cape Floral Region are additionally appealing because in contrast to the many geophytes that are highly fibrous, they are low in fiber relative to the amount of energy-rich carbohydrate they contain, making them more easily digested by children. (Cooking further enhances their digestibility.) And because geophytes are adapted to dry conditions, they would have been readily available during arid glacial phases. Recent studies in South Africa show that many of these species are easy to procure and rich in calories.

The southern coast also has an excellent source of protein to offer. Just offshore, the collision of nutrient-rich cold water from the Benguela upwelling and the warm Agulhas current creates a mix of cold and warm eddies along the southern coast. This varied ocean environment nurtures diverse and dense beds of shellfish in the rocky intertidal zones and sandy beaches. Shellfish are a very high quality source of protein and omega-3 fatty acids. And as with geophytes, glacial cooling does not depress their numbers. Rather, lower ocean temperatures result in a greater abundance of shellfish. Recent research by our team has shown that a third food resource was present during these glacial phases: large-bodied mammals such as antelope and zebra. When sea levels dropped, a plain was exposed in front of the caves, and our study shows that grasslands dominated this plain, and herds of large mammals moved across these grasslands. The region, in short, provided an unprecedented concentration of three major food types during glacial periods.

Gone Shellfishing

Shellfish, which are rich in protein, are thought to have aided survival of the Pinnacle Point population because they abound year-round in the rocky intertidal zone along the southern coast of Africa (1). Brown mussels (2) have turned up in even the earliest levels of PP13B, dating to 164,000 years ago, revealing that humans began exploiting marine resources earlier than previously thought. In addition to mussels, the occupants of the Pinnacle Point sites collected various kinds of limpets as well as sea snails called alikreukel for food and gathered empty shells of helmet snails for their aesthetic appeal (3).

Credit: J. C. DE VYNCK Center for Coastal Paleosciences, Nelson Mandela University

Survival skills

Even without antelope, the southern coast, with its combination of calorically dense, nutrient-rich protein from the shellfish and low-fiber, energy-laden carbs from the geophytes, would have provided an ideal diet for early modern humans during glacial stage 6. Furthermore, women could obtain both these resources on their own, freeing them from relying on men to provision them and their children with high-quality food. We have yet to unearth proof that the occupants of PP13B were eating geophytes—sites this old rarely preserve organic remains—although younger sites in the area contain extensive evidence of geophyte consumption. But we have found clear evidence that they were dining on shellfish. Studies of the shells found at the site conducted by Antonieta Jerardino, then at the University of Barcelona, show that people were gathering brown mussels and local sea snails called alikreukel from the seashore. They also ate marine mammals such as seals and whales on occasion.

Previously the oldest known examples of humans systematically using marine resources dated to less than 120,000 years ago. But dating analyses performed by Miryam Bar-Matthews of the Geological Survey of Israel and Zenobia Jacobs of the University of Wollongong in Australia have revealed that the PP13B people lived off the sea far earlier than that: as we reported in 2007 in the journal Nature, marine foraging there dates back to a stunning 164,000 years ago. By 110,000 years ago the menu had expanded to include species such as limpets and sand mussels.

This kind of foraging is harder than it might seem. The mussels, limpets and sea snails live on the rocks in the treacherous intertidal zone, where an incoming swell could easily knock over a hapless collector. Along the southern coast, safe harvesting with sufficiently high returns is only possible during low spring tides, when the sun and moon align, exerting their maximum gravitational force on the ebb and flow of the water. Because the tides are linked to the phases of the moon, advancing by 50 minutes a day, I surmise that the people who lived at PP13B—which 164,000 years ago was located much farther inland, two to five kilometers from the water, because of lower sea levels—scheduled their trips to the shore using a lunar calendar of sorts, just as modern coastal people have done for ages. A recent study by Jan De Vynck of Nelson Mandela University found that skilled coastal foragers could harvest shellfish at return rates that exceed the former king of return-rate foraging—large mammal hunting!

Digging for Dinner

Geophytes, the underground energy-storage organs of certain kinds of plants (4), swell with edible carbohydrates at certain times of the year. The distinctive vegetation that hugs the southern coast of Africa, particularly the fynbos plants (5), produces especially nutritious and easily digested geophytes, which presumably served as a staple for the early modern humans who lived in this region during glacial stage 6.

Credit: J. C. DE VYNCK Center for Coastal Paleosciences, Nelson Mandela University

Harvesting shellfish is not the only advanced behavior in evidence at Pinnacle Point as early as 164,000 years ago. Among the stone tools are significant numbers of “bladelets”—tiny flakes twice as long as they are wide—that are too small to wield by hand. Instead they must have been attached to shafts of wood and used as projectile weapons. Composite toolmaking is indicative of considerable technological know-how, and the bladelets at PP13B are among the oldest examples of it. But we soon learned that these tiny implements were even more complex than we thought.

Most of the stone tools found at coastal South African archaeological sites are made from a type of stone called quartzite. This coarse-grained rock is great for making large flakes, but it is difficult to shape into small, refined tools. To manufacture the bladelets, people used fine-grained rock called silcrete. There was something odd about the archaeological silcrete, though, as observed by Kyle S. Brown, now at the University of Cape Town, an expert stone tool flaker on my team. After years of collecting silcrete from all over the coast, Brown determined that in its raw form the rock never has the lustrous red and gray coloring seen in the silcrete implements at Pinnacle Point and elsewhere. Furthermore, the raw silcrete is virtually impossible to shape into bladelets. Where, we wondered, did the toolmakers find their superior silcrete?

A possible answer to this question came from another site we are excavating, Pinnacle Point Cave 5-6 (PP5-6), where one day in 2008 we found a large piece of silcrete embedded in ash. It had the same color and luster seen in the silcrete found at other archaeological deposits in the region. Given the association of the stone with the ash, we asked ourselves whether the ancient toolmakers might have exposed the silcrete to fire to make it easier to work with—a strategy that has been documented in ethnographic accounts of native North Americans and Australians. To find out, Brown carefully “cooked” some raw silcrete and then attempted to knap it. It flaked wonderfully, and the flaked surfaces shone with the same luster seen in the artifacts from our sites. We thus concluded that the Stone Age silcrete was also heat-treated.

We faced an uphill battle to convince our colleagues of this remarkable claim, however. It was archaeology gospel that the Solutrean people in France invented heat treatment about 20,000 years ago, using it to make their beautiful tools. To bolster our case, we used three independent techniques. Chantal Tribolo of the University of Bordeaux Montaigne performed what is called thermoluminescence analysis to determine whether the silcrete tools from Pinnacle Point were intentionally heated. Then Andy Herries, at the time at the University of New South Wales in Australia, employed magnetic susceptibility, which looks for changes in the ability of rock to be magnetized—another indicator of heat exposure among iron-rich rocks. Finally, Brown used a gloss meter to measure the luster that develops after heating and flaking and compared it with the luster on the tools he made. Our results, published in 2009 in Science, showed that intentional heat treatment was a dominant technology at Pinnacle Point by 72,000 years ago and that people there employed it intermittently as far back as 164,000 years ago. In 2012 in a study in Nature we showed that Pinnacle Point residents employed an entirely new technique of stone tool manufacture, called microlithic technology, far earlier than anywhere else in the world. This technology allows one to make very small, light stone weapons and represents a breakthrough in the lethality of armaments.

The process of treating by heat testifies to two uniquely modern human cognitive abilities. First, people recognized that they could substantially alter a raw material to make it useful—in this case, engineering the properties of stone by heating it, thereby turning a poor-quality rock into high-quality raw material. Second, they could invent and execute a long chain of processes. The making of silcrete blades requires a complex series of carefully designed steps: building a sand pit to insulate the silcrete, bringing the heat slowly up to 350 degrees Celsius, holding the temperature steady and then dropping it down slowly. Creating and carrying out the sequence and passing technologies down from generation to generation probably required language. Once established, these abilities no doubt helped our ancestors outcompete the archaic human species they encountered once they dispersed from Africa. In particular, the complex pyrotechnology detected at Pinnacle Point would have given early modern humans a distinct advantage as they entered the cold lands of the Neandertals, who seem to have lacked this technique. When combined with a new form of extreme cooperation and the advanced projectiles made possible by microlithic technology, modern humans swept out of Africa and conquered the planet [see “The Most Invasive Species of All,” by Curtis W. Marean; Scientific American, August 2015].

Smart from the start

In addition to being technologically savvy, the prehistoric denizens of Pinnacle Point had an artistic side. In the oldest layers of the PP13B sequence, my team has unearthed dozens of pieces of red ochre (iron oxide) that were variously carved and ground to create a fine powder that was probably mixed with a binder such as animal fat to make paint that could be applied to the body or other surfaces. Such decorations typically encode information about social identity or other important aspects of culture—that is, they are symbolic. Many of my colleagues and I think that this ochre constitutes the earliest unequivocal example of symbolic behavior on record and pushes the origin of such practices back by tens of thousands of years. Evidence of symbolic activities also appears later in the sequence. Deposits dating to around 110,000 years ago include both red ochre and seashells that were clearly collected for their aesthetic appeal because by the time they washed ashore from their deepwater home, any flesh would have been long gone. I think these decorative seashells, along with the evidence for marine foraging, signal that people had, for the first time, begun to embed in their worldview and rituals a clear commitment to the sea.

The precocious expressions of both symbolism and sophisticated technology at Pinnacle Point have major implications for understanding the origin of our species. Fossils from Ethiopia show that anatomically modern humans had evolved by at least 195,000 years ago, and newly dated fossils found long ago in Morocco suggest the species may date back to 300,000 years ago. The emergence of the modern mind, however, is more difficult to establish. Paleoanthropologists use various proxies in the archaeological record to try to identify the presence and scope of cognitive modernity. Artifacts made using technologies that require outside-the-box connections of seemingly unrelated phenomena and long chains of production—like heat treatment of rock for tool manufacture—are one proxy. Evidence of art or other symbolic activities is another, as is the tracking of time through proxies such as lunar phases. For years the earliest examples of these behaviors were all found in Europe and dated to after 40,000 years ago. Based on that record, researchers concluded that there was a long lag between the origin of our species and the emergence of our peerless creativity.

Cutting-Edge Technology

Stone tools found in PP13B include sophisticated implements such as microblades (bottom two rows), which would have been attached to a wood shaft to form projectile weapons. The toolmakers also appear to have heat-treated the stone to make it easier to shape—a technique that was believed to have originated much later and in France.

Credit: J. C. DE VYNCK Center for Coastal Paleosciences, Nelson Mandela University

But over the past 25 or so years archaeologists working at a number of sites in South Africa have found examples of sophisticated behaviors that predate by a long shot their counterparts in Europe. For instance, archaeologist Ian Watts, who works in South Africa, has described hundreds to thousands of pieces of worked and unworked ochre at sites dating as far back as 120,000 years ago. Interestingly, this ochre, as well as the pieces at Pinnacle Point, tends to be red despite the fact that local sources of the mineral exhibit a range of hues, suggesting that humans were preferentially curating the red pieces—perhaps associating the color with menstruation and fertility. Jocelyn A. Bernatchez, then at Arizona State University, thinks that many of these ochre pieces may have been yellow originally and then heat-treated to turn them red. And at Blombos Cave, located about 100 kilometers west of Pinnacle Point, Christopher S. Henshilwood of the Universities of Bergen in Norway and Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, in South Africa has discovered pieces of ochre with systematic engravings, beads made of snail shells and refined bone tools, all of which are older than 70,000 years ago. These sites, along with those at Pinnacle Point, belie the claim that modern cognition evolved late in our lineage and suggest instead that our species had this faculty at its inception.

I suspect that a driving force in the evolution of this complex cognition was strong long-term selection acting to enhance our ancestors’ ability to mentally map the location and seasonal variation of many species of plants in arid environments and to convey this accumulated knowledge to offspring and other group members. This capacity laid the foundation for many other advances, such as the ability to grasp the link between the phases of the moon and the tides and to learn to schedule their shellfish-hunting trips to the shore accordingly. Together the readily available shellfish and other abundant foods provided a high-quality diet that allowed people to become less nomadic, increased their birth rates and reduced their child mortality. The larger group sizes that resulted from these changes would have promoted symbolic behavior and technological complexity as people endeavored to express their social identity and build on one another’s technologies, explaining why we see such sophisticated practices at PP13B.

Probing the Past

Continued excavation of PP13B (shown here) and other caves along the southern coast of Africa should reveal more about the progenitor population of humans who survived the population bottleneck and went on to colonize the globe.

Credit: J. C. DE VYNCK Center for Coastal Paleosciences, Nelson Mandela University

Follow the sea

PP13B preserves a long record of changing occupations that, in combination with the detailed records of local climate and environmental change my team has obtained, is revealing how our ancestors used the cave and the coast over millennia. Modeling the paleocoastline over time, Erich C. Fisher, now at Arizona State, has shown that the conditions changed quickly and dramatically, thanks to a long, wide, gently sloping continental shelf off the coast of South Africa called the Agulhas bank. During glacial periods, when sea levels fell, significant amounts of this shelf would have been exposed, putting considerable distance—up to 95 kilometers—between Pinnacle Point and the ocean. When the climate warmed and sea levels rose, the water advanced over the Agulhas bank again, and the caves were seaside once more.

Recent research by our group shows that when the sea retreated, a grassland formed close to the caves, and the fynbos persisted north of the caves. So when the coast was moderately distant, there was an exceptionally rich confluence of food resources for people: geophytes from the fynbos, shellfish from the sea and large game animals on the grasslands. When the coast retreated farther away, people followed the sea so that they always had access to coastal foods. We recently showed in an article in Nature in March 2018 that people here thrived through the Toba megavolcanic eruption—it seems likely that the rich resource base made this possible.

Our excavations at PP13B have intercepted the people who may very well be the ancestors of everyone on the planet as they shadowed the shifting shoreline. Yet if I am correct about these people and their connection to the coast, the richest record of the progenitor population lies underwater on the Agulhas bank. There it will remain for the near future, guarded by great white sharks and dangerous currents. We can still test the hypothesis that humans followed the sea by examining sites on the current coast such as PP13B and PP5-6. But we can also study locations where the continental shelf drops steeply and the coast was always near—investigations that Fisher is currently running on the eastern coast of Africa in Pondoland.

The genetic, fossil and archaeological records are reasonably concordant in suggesting that the first substantial and prolonged wave of modern human migration out of Africa occurred around 70,000 years ago. But questions about the events leading up to that exodus remain. We still do not know, for example, whether at the end of glacial stage 6 there was just one population of H. sapiens left in Africa or whether there were several, with just one ultimately giving rise to everyone alive today.

Such unknowns are providing my team and others with a very clear and exciting research direction for the foreseeable future: our fieldwork needs to target the other potential progenitor zones in Africa during that glacial period and expand our knowledge of the climate conditions just before that stage. We need to flesh out the story of these people who eventually pushed out of their refuge, filled up the African continent and went on to conquer the world.